What the sitting-rising test says about your health

Learn the surprising implications of a simple assessment, especially for women.

- Reviewed by Toni Golen, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Women's Health Watch; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing; Contributor

We all rise from sitting to standing perhaps dozens of times each day, underscoring how essential this fundamental movement is to our ability to live normally.

But while most of us usually get up from a chair, a test gauging our ability to rise from the floor — which, for many, is far more challenging — is increasingly becoming a crucial health barometer, particularly for women.

How easily you can rise to your feet from sitting on the floor, using as little support as possible, may help predict your longevity, according to a study published online June 18, 2025, by the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology.

“Especially as folks age, this is something they’re very concerned about: if they’re playing with their grandchildren on the ground or somehow end up there, are they going to be able to stand up when they need to without help?” says Mary Kate Miller, the clinical supervisor of physical therapy at Harvard-affiliated Spaulding Rehabilitation Outpatient Center Malden. “It’s so important to be able to do this, whether we intentionally or unintentionally get on the floor.”

Fundamental fitness components

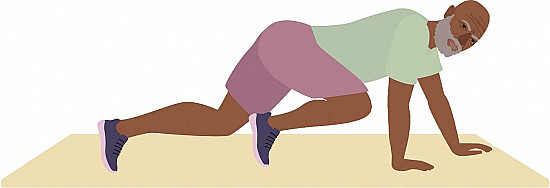

To score a perfect 10 points on the sitting-rising test, you need to be able to get up from a seated position on the floor without using your hands, forearms, knees, or the sides of your legs for support. You must also remain steady. If you wobble, or need to kneel or place a hand on the floor to support yourself, you begin to lose points. And if you can’t do it without relying on help from a wall, chair, table, or another person, your score drops to zero.

For the study, researchers analyzed data from nearly 4,300 people ages 46 to 75 (32% women) who completed the sitting-rising test as part of a voluntary fitness assessment. None had physical issues or diagnosed conditions that would restrict their abilities. After an average follow-up of 12 years, researchers found that participants who scored the lowest (0 to 4 points) were nearly four times more likely to have died overall and six times more likely to have died of cardiovascular causes than people who scored a 10.

“Folks who can stand up from the ground, with less support or assistance, generally have much better cardiovascular and strength conditioning,” Miller says. “We also know these are indicators of longevity — whether from decreasing the risk of other causes of death or from staying generally healthier as you age.”

What does it take to ace the sitting-rising test? Not just strength, but several other elements of fitness that don’t necessarily result from aerobic exercise, Miller notes. These include coordination, flexibility, and balance.

But these components begin to decline surprisingly early in life—around age 35 or 40 — and drop off more precipitously in women, Miller says. We also face far higher indoor fall risks than men, meaning at some point we may need to be able to get up from the floor.

“Unfortunately, the hormonal changes that come with female aging, especially through menopause, magnify this problem,” Miller says. “We see a larger detrimental change in women — a greater loss in muscle mass and increase in fat storage that makes it harder to move the way you want.”

The importance of strength training

“Being fit” is often considered synonymous with aerobic fitness — which comes from activity that boosts heart rate, breathing, and blood flow. But this study spotlights the equal importance of other types of exercise as we age, Miller says.

“Strength training keeps muscles strong in a way that walking and cardiovascular conditioning just doesn’t,” she says. “When it comes to being able to stand up from the ground or a low chair — or one of those couches that you sink into when you sit on it — you can walk as many miles as you want, but that’s not going to keep muscles strong enough to do the tougher activities you don’t have to do as often.”

You likely know intuitively if you’d be able to perform the sitting-rising test without a problem. But if you’re not sure, don’t try it at home — instead, talk it through with your primary care doctor. She can then help you address any deficits in strength, balance, coordination, or flexibility through a new fitness program or physical therapy.

“If you fear ending up on the ground without being able to get up, the best thing you can do is find a physical therapist to help you,” Miller says.

This article is brought to you by HarvardHealthOnline+, the trusted subscription service from Harvard Medical School. Subscribers enjoy unlimited access to our entire website, including exclusive content, tools, and features available only to members. If you're already a subscriber, you can access your library here.

Image: © pixelfit/Getty Images

About the Author

Maureen Salamon, Executive Editor, Harvard Women's Health Watch

About the Reviewer

Toni Golen, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Women's Health Watch; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing; Contributor

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.