A brief fitness test may predict how long you’ll live

The sit-to-rise test assesses your strength, flexibility, and balance, which are important (but sometimes overlooked) aspects of fitness.

- Reviewed by Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Can you sit down on the floor and stand back up again without using your hands, your knees, furniture, or another person for support or assistance? If so, that bodes well for your longevity. According to a study published June 18, 2025, by the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, middle-aged and older people who can do the sit-to-rise test without support are less likely to die (especially of cardiovascular disease) within the following decade.

The study included 4,282 people ages 46 to 75 who did the sit-to-rise test as part of a medical evaluation; researchers then tracked them for an average of about 12 years. The test is scored by starting with 10 points and then subtracting one point every time a person uses a hand, knee, or other support, and a half point every time the person is unsteady or wobbly. Compared to people who scored a 10 (no supports or wobbling), those who scored between 4.5 and 7.5 were about three times as likely to die during the follow-up period. And those who scored 0 to 4 had six times the risk of dying of cardiovascular disease.

“The test is a good way to assess your strength, flexibility, and balance, all of which are vital for staying active and functioning well as you age,” says Eric L’Italien, a physical therapist with Harvard-affiliated Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital. Many people focus mainly on aerobic exercise like brisk walking to stay fit and pay less attention to those other aspects of fitness. Doing strength-building exercises at least twice a week can help, while yoga and tai chi are good ways to improve balance and flexibility.

How to do the test

First, don’t try this test if you have disabilities or joint problems, like hip, spine, or knee arthritis. And don’t do it alone — find a partner to track your score and lend a hand or other support if needed. Wear loose-fitting, comfortable clothes but no shoes or socks, and do the test on a carpet or yoga mat.

Stand with your feet slightly apart and cross one foot in front of the other, keeping your arms in any position. Taking your time, slowly lower yourself until you’re seated on the ground. Then try to stand back up. For many older people, getting down and up from the floor can be challenging, so don’t feel disheartened if you need to use supports. In fact, L’Italien recommends erring on the side of caution and using your hands and knees (or even a nearby wall or sturdy chair) the first time you try it. “Do the easiest possible version to start, and then gradually work toward using fewer supports,” he suggests.

3 exercises to boost your score

To improve your score, here are three exercises L’Italien recommends.

1. Stationary lunges

These help improve leg strength and balance. Stand up straight with your right foot one to two feet in front of your left foot, hands on your hips. Shift your weight forward and lift your left heel off the floor. Bend your knees and lower your torso straight down until your right thigh is about parallel to the floor. Hold, then return to the starting position. Do this five to 10 times with each leg to make a set. Do two to three sets.

Modification: Stand next to a countertop or wall for hand support.

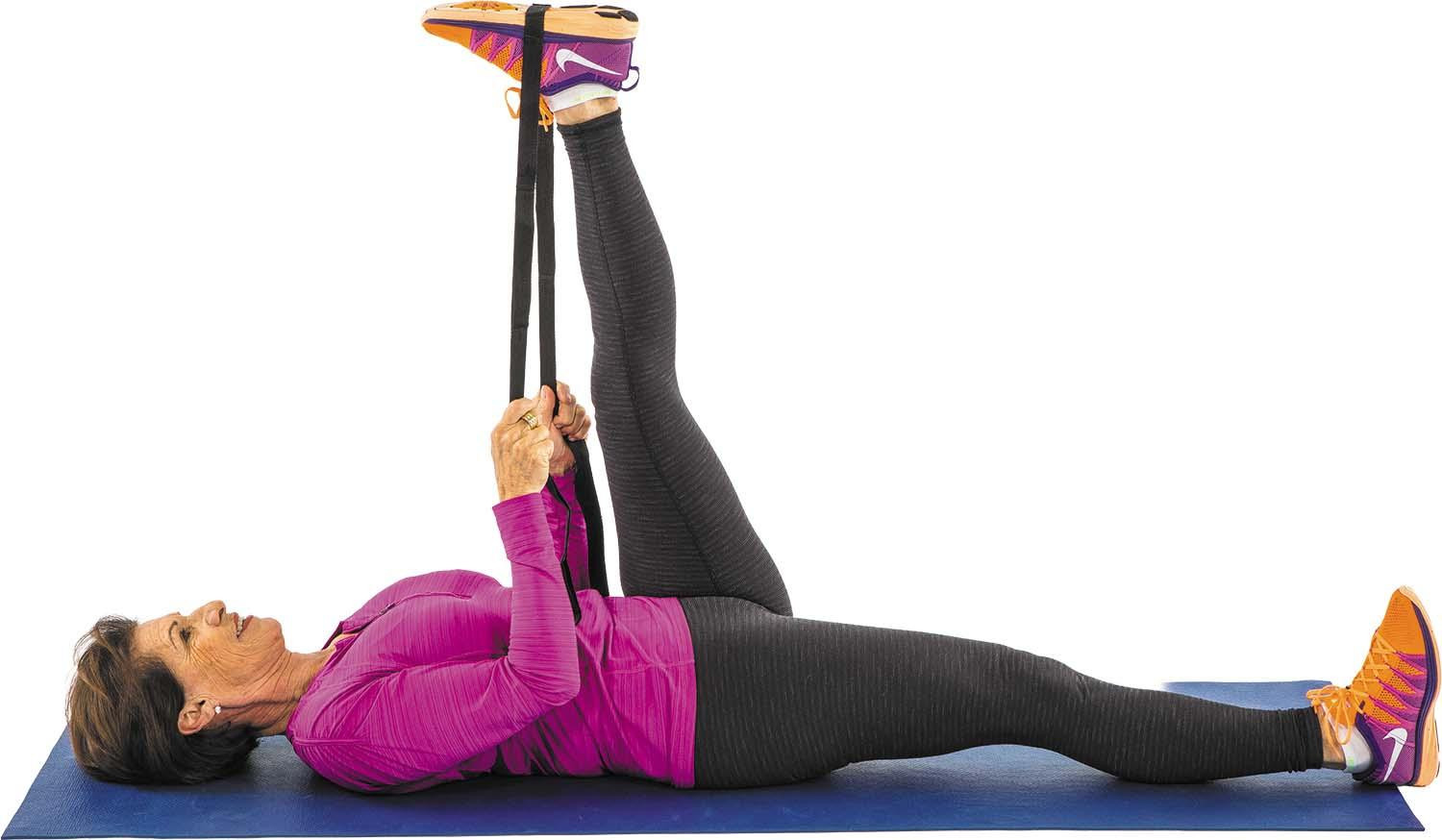

2. Hamstring stretch

Tight hamstrings are one of the most common reasons older adults aren’t very flexible. Lie on your back and place a strap, belt, or towel around one foot. Holding the strap, gently pull the leg back toward your head until you feel a stretch in the back of the thigh. Hold the stretch for 30 seconds and then release. Switch to the other leg and repeat.

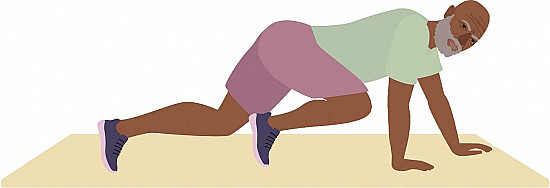

3. Plank

This can help strengthen a weak core. Lie face down with your forearms resting on the floor. Raise your body up, so it forms a straight line from your head and neck to your feet. Tighten your belly and try to hold this position for 10 seconds. Rest and then repeat. Do two to three planks in total. Work up to holding each plank for 30 seconds or longer.

Modification: Keep your knees on the floor, or do it while leaning against a counter or table at a 45° angle.

This article is brought to you by HarvardHealthOnline+, the trusted subscription service from Harvard Medical School. Subscribers enjoy unlimited access to our entire website, including exclusive content, tools, and features available only to members. If you're already a subscriber, you can access your library here.

Exercise photos by Thomas MacDonald and Michael Carroll

About the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

About the Reviewer

Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.