What’s new in blood clot prevention?

Strategies include low-dose drug combinations and new agents that are less likely to cause bleeding.

- Reviewed by Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

If a blood clot lodges in an artery or vein, it can choke off blood flow to the heart, brain, or lung. The potential consequences can be devastating — a heart attack, stroke, or pulmonary embolism. “It’s the reason that clot-preventing drugs play such a large role in caring for people with cardiovascular disease,” says cardiologist Dr. Gregory Piazza, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Although often referred to as blood thinners, anti-clotting drugs (see “Common anti-clotting drugs”) don’t actually make your blood less viscous. But because they interfere with the body’s natural clotting process, even minor injuries (like cuts and bruises) may bleed more easily. Less common but more worrisome is internal bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract or brain. The trick is finding the right balance between helpful and harmful clotting. New solutions are in the works.

Common anti-clotting drugsAnticoagulant drugs. These include warfarin and the following direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs):

Antiplatelet drugs

|

Clot disruption: Good vs. bad

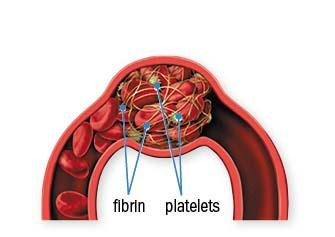

Anti-clotting drugs interfere with one of two key components involved in clot formation: fibrin and platelets (see “Anatomy of a blood clot”).

- Anticoagulants. These inhibit the creation of fibrin, treat clots in the legs (deep-vein thrombosis) and the lungs (pulmonary embolism). They’re also prescribed to people with atrial fibrillation, a rapid, irregular heart rhythm that causes blood to pool in the heart’s upper chambers, raising the risk of clots.

- Antiplatelet drugs. These are used to prevent heart attacks and strokes and to treat people who receive stents, the tiny metal mesh tubes placed in clogged blood vessels.

Anti-clotting drugs don’t cause bleeding per se. Rather, the bleeding results from a breach in the wall of a blood vessel, which may trigger only microscopic amounts of bleeding at first. But it may continue unabated and become more serious over time. Anyone taking these medications should pay attention to even minor bleeding, says Dr. Piazza.

Anatomy of a blood clotBlood clots consist of two key components:

Together, they stabilize clots, keeping them from falling apart. Clots that form in the veins are made mostly of fibrin. If such a clot forms in a deep vein of a leg or arm or in the abdomen it’s known as a deep-vein thrombosis, or DVT. Clots in the arteries, on the other hand, tend to contain more platelets. These tend to form in the arteries feeding the heart and brain, as well as the legs. |

Minor versus major bleeding

What are the warning signs? Some people notice bleeding gums after toothbrushing or flossing, or they have nose-bleeds that take longer than usual to stop. Frequent or large bruises (especially on the trunk of the body) are another potentially worrisome sign. Be sure to mention these symptoms to your doctor.

See a doctor right away if you have more serious symptoms. These include

- tea-colored, pink, or red urine (possible bleeding in the urinary tract)

- stools that are black and tarry or red (possible gastrointestinal bleeding)

- a sudden, very bad headache (possible bleeding in the brain).

You should also get medical attention if you fall or get hit hard, even if there’s no visible blood, says Dr. Piazza. Finally, be aware that common over-the-counter pain relievers such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), and naproxen (Aleve) can interact with anti-clotting drugs. Check with your doctor if you take these drugs often.

New strategies

Efforts are under way to maximize clot prevention and minimize the bleeding risk. “There’s increasing interest in combining low doses of anticoagulant and antiplatelet drugs together,” says Dr. Piazza. In some situations, this hybrid approach appears to prevent clot-related problems better than a higher dose of a single drug.

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) work by preventing the action of key enzymes in the blood-clotting process. For example, apixaban (Eliquis) and rivaroxaban (Xarelto) block a protein called factor Xa. Several new anticoagulants that target a different one, factor XI, have been tested in a number of different scenarios, including atrial fibrillation. So far, some appear promising for preventing clots with a lower risk of bleeding, says Dr. Piazza.

Image: © wildpixel/Getty Images

About the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

About the Reviewer

Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.