Can you slow down stenosis of the aortic valve?

Ask the doctor

Q. I’m 80 years old and recently had an echocardiogram that showed mild aortic stenosis (my mean pressure gradient value is 13). I walk and swim regularly without any issues. Is there anything I can do to slow down the deterioration of my aortic valve? Are there any medications that can improve its function?

A. Aortic stenosis (narrowing of the aortic valve) is fairly common in older adults, affecting about 10% of people by the age of 80. Interestingly, the exact cause is not well understood. But certain health problems may increase a person’s odds of aortic stenosis, including kidney disease, hyperparathyroidism, and inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis. High LDL cholesterol and elevated levels of another type of “bad” cholesterol, known as Lp(a), have also been linked to a higher risk of aortic stenosis.

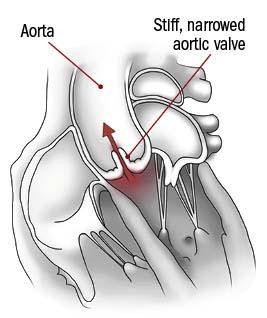

The aortic valve sits between the left ventricle (the heart’s main pumping chamber and the aorta (the body’s main artery; see illustration). When the valve narrows, the average pressure in the left ventricle is higher compared with the aorta. You have mild stenosis, which is defined as a mean pressure gradient of 20 or lower. If a person’s mean pressure value gets to 50 or 60, however, that puts a great deal of strain on the left ventricle and limits how much blood gets through the valve to the body. When that happens, the valve needs to be replaced.

In terms of what you can do, stick with what you’re already doing — staying active and exercising regularly. While this may not directly benefit your valve, exercise will help keep your arteries functioning well, which in turn will help your heart respond to any increase in your pressure gradient over time. With your relatively mild stenosis, I am hopeful it won’t progress too much.

Currently, there are no medications to prevent or treat aortic stenosis, but there are some possibilities in the pipeline. One clinical trial that tested a combination of two LDL-lowering drugs showed no benefit in slowing progression of aortic stenosis. But as expected, the drugs did lower the risk of heart attack, stroke, and death from heart disease. Ongoing trials are testing whether some of the new experimental agents that lower Lp(a) by as much as 80% or more have any effect on aortic stenosis in people who also have high Lp(a) levels. In addition, a recent study found that a class of drugs used to treat diabetes, known as SGLT-2 inhibitors, seem to reduce the progression of mild to moderate aortic stenosis over a five-year period, but further research is needed. Finally, research on another new drug is proceeding (see “Drug to slow aortic stenosis shows early promise” in the June 2025 Heart Letter).

Illustration by Galiya Kolnsberg

About the Author

Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.